As wine regions go, Napa Valley is quite new to the world stage and thus considered part of the New World of wine. Still, its history is rich with the stuff of classic dramas: struggle, success, near defeat, and ultimate victory.

In the late 19th century, thousands flocked to California for the Gold Rush. Many of the miners settled in San Francisco and eventually started new ventures north of the city – planting vineyards. The original Napa Valley wine boom occurred between 1860 to 1890, when more than 140 wineries were operating in the area. The region was booming, wineries were winning international awards, and more and more land was being planted to grapes. But a series of events over the next decades almost killed any hope for the California wine country as we know it today.

Some of the misfortune wasn’t unique to California, or America. Phylloxera, a vineyard disease that had wiped out vast expanses of European vineyards, hit America, effectively killing decades of vineyard growth and closing many wineries. It’s estimated that phylloxera destroyed more than 80% of Napa Valley grapevines by 1900.

Just beginning to rebound from this episode, The US passed the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, making illegal the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors, within the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof, from the U.S. …for beverage purposes”—what we know as Prohibition.

Although most wineries shuttered their doors over the next 14 years, those wineries that managed to stay in business during this time grew rich.

The Volstead Act provided loopholes to Prohibition, excluding wine used for religious purposes, and homemade fruit juice for personal use – up to 200 gallons per year. Two of the oldest wineries in Napa Valley found a way to succeed in this period. Beaulieu Vineyard survived prohibition by negotiating an exclusive deal to supply wine to the churches of the San Francisco diocese, and Beringer Vineyards utilized the Volstead loophole to make wine for religious purposes too.

Inglenook, now owned by Francis Ford Coppola, survived Prohibition by selling wine grapes directly to consumers when operations ceased. Other winery owners sold grapes, grape juice, and raisin cakes to make a living. But the great majority of wineries and vineyards ceased to operate.

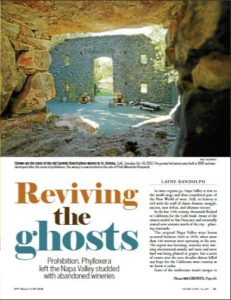

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, only 40 wineries had managed to survive and hundreds were left abandoned. Called “ghost wineries,” most were lost forever, but a precious few were later restored to their former glory. These wineries make up some of the oldest, most iconic, and cherished properties today.

Far Niente is one of California’s oldest wineries and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It was shuttered during Prohibition and remained abandoned until it was restored in 1979. Charles Krug Winery was founded in 1861 and became the first commercial winery in Napa Valley, and the first public tasting room in California. The winery made it through Prohibition before being purchased by Cesare Mondavi in 1943. It took almost a decade to make the property operational again, and it remains one of the oldest wineries in Napa Valley.

The Napa Valley offers more than world-renowned wine. The region’s incredible history has made it what it is today, and the modern-day presence of ghost wineries is a constant reminder of how far it’s come.

Layne Randolph, Inside Napa Valley, July 2019